|

The

Jelly Connection

It may well have been the description that did it. I had said that Beroe was nothing more than "a pair or lips attached to a stomach". No Star Wars character could "hold a light" to it. Inspired by Howard and Michelle Hall's intriguing article in the December 1998 issue of Ocean Realm, it seemed appropriate to contribute another strange photographic assignment from the opposite side of the world which we too were filming for the same NOVA IMAX film, "Island of Sharks". The difference was that our "sharks" swallowed their victims whole! In Vancouver at the 1997 Large Film Format Conference (ISTC as it was then called), Suzi, my wife, and I renewed time, news and experience with Howard and Michelle, whom we'd known by then for some years, but seldom got to see, living on opposite sides of the pond as we do and being often beneath different oceans. Both Howard and Michelle and our close colleagues at NOVA WGBH asked us if Image Quest 3-D, our small company, would consider contributing a small but somewhat unusual sequence to their forthcoming film "Island of Sharks". Howard's idea was to devote a little bit of the precious 40 minutes of the film to explaining why sea mounts seem to act as the focus of attention for a great many top predators in the oceanic food chain. Steep-sided sea mounts cause oceanic currents to well-up from deep water, bringing colder mineral-rich waters closer to the surface around these undersea mountains. The rising nutrients in turn propagate vast increases in the plankton community which in turn bring in the planktonivores such as fusiliers, anchovy, herring, sardines, hardiheads, flying fish and mid deep water forms like myctophid lantern fish. These shoaling fish attract, in their turn, tuna, billfish, mackerel, barracuda and of course sharks. Howard's thinking was that it would be great to show not only the plankton community as a whole but also some of the bizarre individuals amongst these upwelling masses of water and, if possible, a predation sequence within that community. He also knew that for nearly eight years we had concentrated our technical efforts into trouble-shooting the numerous optical problems associated with achieving magnifications of up to half a million times onto the enormous 125' Imax screen, in both 2-D and 3-D. He knew also that we did a lot of work in the tropics of both Atlantic and Pacific oceans and that we had spent over 30 years compiling a huge library of marine planktonic species in both stills and movie. It was in a corner of the conference, with reference to some of this past material, that we fairly quickly homed-in on what might be best to attempt from Lizard Island on The Great Barrier Reef while he, Michelle and their team were battling away off Cocos Island. The climax we devised for this small sequence was to show one of the very predacious Beroid comb jellies devouring one of its cousins. Howard and I had both seen this sort of behavior in the wild. The challenge now would be to capture it on film, with all the drama of flashing comb plates and whole-animal-swallowing. The decision was made not to have the Beroe occupy more than a quarter of the frame - even so, at that size on the film it would still be ten meters across on the screen! We didn't realize it then, but our task five months later was going to be further aggravated not only by a paucity of animals, but also the few we did find were one tenth the size we had anticipated. February 1998 saw four of the team arriving on Lizard Island with 60 crates of equipment weighing in at one and a half tons - a cool £10,000 worth of return airfreight before we'd even begun. Four days of equipment-construction and assembly later and we were ready to go. We had five weeks - the wet season upon us, but high hopes that if we gave the deep water channel all out attention day and half the night we'd find "lips" Beroe! Chris Parks and Justin Peach were my filming, diving and drifting partners. Chris was mainly covering the stills both in 2-D and 3-D while Justin assisted me with the Imax camera and all its fads and foibles. The three of us sought, collected, maintained and nurtured our precious animals and cleaned, tuned and tweaked the specialized Kreisel tanks we had designed, built and brought. I took sole responsibility for the really high magnification work. Our very first drift search in the Deep Water Channel brought us a surprise result. The weather was bright and breezy and the water choppy. The prevailing twenty knot S.E. trade gave our 16' Zodiac a healthy turn of speed when adrift in the main channel. We trailed mountaineering ropes into the blue waters, kitted-up and slithered in with self-seal polythene bags. "Slithering" always seemed to make sense when entering waters well populated with sharks of almost every species known to man. You feel a bit vulnerable pretending to be a comb jelly within a meter of the surface out there! In the old days we used to lower our anchor as a drogue. It never anywhere near reached the bottom but it slowed the speed of drift. Nowadays we kept our anchor in-board and used the speed of drift to survey a wider swathe of ocean. Chris and Justin both learnt to surf towards the boat with the aid of the ropes and the prevailing wind and on several occasions more or less landed in the boat clutching a polybag with diaphanous content. That first drift found us surrounded by small lobate ctenophores. These we had anticipated and we were gratified to find our season-choice had been appropriate in spite of a 3-week delay while lawyers processed contracts every which way but loose! However our gratification turned to surprise when we realized these were not Mnemiopsid comb jellies but small Leucotheca. This intrigued us. In thirty years I had only seen three Leucotheca off Lizard Island - one large one on my very first Outer Barrier dive in 1978, one medium sized one that Justin caught on a previous trip and one monster I had found fifteen feet below my inflatable while I was alone in flat calm conditions right where we were now, but hovering above a pair of grey reef sharks. On this latter occasion I so wanted to dive in, grab it and bring it ashore, but not only was it too large to catch, but the shark and my solitary condition all conspired to make me a wimp. I did however bravely paddle slowly along above the beautiful creature. I began then to realize it was slowly rising to the surface. Up and up it came and at about four feet from the surface I thought I would try wafting it further still towards the surface. I had a hand net and with this I began gently upwelling the water next to the comb-jelly.Suddenly the current got to it and to my horror the creature exploded into several thousand fragments! Most marine biologists have some story like this with comb jellies and not one of us can offer an explanation - spontaneous fragmentation! How? Why? It's a mystery. So with Chris and Justin returning to the boat with dozens of young gooseberry-sized Leucotheca you can imagine the mounting excitement. If we now got loads of the common Mnemiopsis and Bolinopsis, a scattering of the sea-gooseberry Pleurobrachia, we'd be sure then to find their predator Beroe in the vicinity. We'd be really well set up for a good start - almost unheard of in Wildlife filming! If we were really lucky, maybe we'd get Neris, a super big Beroid with outriggers like an X-wing and an orange streak down each side. I had found a few of these on previous trips and spent twenty years trying to find their name. They are very rarely seen and the number of marine biologists with the ability to name them can be numbered on the fingers of one hand. When these open their lips they could swallow a fist!

We did not know it, but little of this was to happen and much of our trip was to be a real struggle to get anything for the film.That same day we also realized, when we hauled in our first live micro-plankton trawl fitted with a special cod-end, designed not to damage our smaller drifting quarry, that the waters around us were full of pea-sized cavoliniid pteropods-small flapping snails that trail huge mucus nets in which they snare micro and phyto planktonic prey and then haul them in to their gullets. Cavolinia always makes us laugh when we see it. It seems so incredibly inefficient - it has to flap like mad to maintain its position in the water column, sinking like a stone should it stop for a moment. This find also took us by surprise. It took us even further by surprise when every haul for the coming five weeks came in clogged solid with Cavolinia. Previous trips had seldom encountered more than the odd one. This trip encountered them so consistently that the beaches were carpeted by their lens-like shells which were distinctly prickly to walk on in bare feet. The "prickles" were in reality the "ears" of the shells through which, in life, the mucous nets were extruded and then withdrawn laden with microscopic prey. What we didn't realize, until we introduced some of them, was that Cavoliniid pteropods comprise one of the comb-jellies' basic diets, shells and all.

Our previous two expeditions to Lizard Island had brought us face to face with incredible populations of the common jellyfish Aurelia. Our first collecting drift on this trip also brought us in a few, plenty enough to film, but no more than a trace of the huge numbers encountered the year before. Our main interest in Aurelia was that because it always pulsed towards the surface it gave a good strong impression of upwardly migrating plankton - important for the context within Howard and Michelle's film. We also had a hidden agenda wish for the Aurelia - one that realistically held only a slim chance of succeeding. From that first drift we decided carefully to scrutinize every Aurelia we bumped into or swam past throughout the rest of the trip. What we were hoping for was to find riding on the back of one of the jellies - a larval lobster or Phyllosoma- literally "leaf-body". Few people ever realize that every spiny lobster, crawfish, or Moreton Bay Bug served up in seafood restaurants around the world, begin their lives as planktonic phyllosoma larvae that ride on the bodies of jellyfish for eighteen months of their lives and drift well out into open oceans. By some means, that biologists still fail to understand, these four centimeter larvae, as flat as a sheet of paper and so transparent that you could read a newspaper through them, ride their jellyfish back into shallower seas and then abandon their hosts, metamorphose into our one centimeter glossy lobsters, spend three or so more days in the plankton, then settle to the sea floor - crawl under suitable cover, become pigmented and by a series of skin changes slowly grow into lobsters.

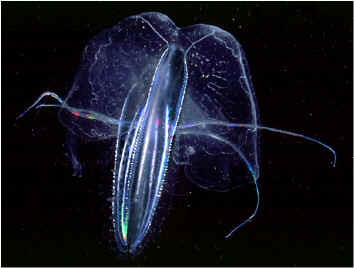

As if this was not enough, at the time they metamorphose the body of the new lobster literally drops out of the body of the phyllosoma and for some hours there are two beings - one big and brainless, but with eyes, legs and mouth parts - the other small, instinctively sharp-witted and with a full compliment of everything. The doomed larval husk flaps aimlessly around until some predator snaps it up and terminates its already failing life. For four weeks we hunted for phyllosomas and then in the same few days Chris caught a couple in the open sea and Justin spotted a couple in the plankton hauls. Pictures seldom do justice to these bizarre creatures, but they are what we achieved and we also had the satisfaction of capturing them for a film screen the size of a five story block of flats. During that first week of our trip we began to realize that 1998 was not only going to give Howard and Michelle problems in Cocos Island but likewise us on Lizard. By then we all knew that for the first time in eleven years, an El Niña was going to occur across the Pacific Ocean contrary to the predictions of those who had successfully predicted its occurrence through the late 80's and most of the 90's. Day by day the weather deteriorated and cyclones began to hover off the N. E. Coast of Queensland. The effect biologically was that nearly everything we had expected, failed to materialise. It took us a week or more to find our first Beroe and when we did eventually find four or five they were no bigger than fingernails. Normally magnification is of little consequence to us, but for this sequence we wanted the animals to have freedom of movement and small comb jellies at magnification were going to give us depth-of-field problems, if they were gliding and drifting in all places of space. So our hope was that the small Beroe were just the prelude to finding bigger, more normal-sized individuals. Search though we did all day, everyday, we found hardly any other specimens and all were dreadfully small. It began to dawn on us that we were going to have to make do with what we had and therefore we were going to have to maintain very carefully and feed our precious beasts for the remaining three weeks of the trip. El Niña, did however produce for us a couple of gems. About two and a half weeks into our trip, while Chris and Justin were out drifting the Deep Water Channel for comb jellies, Justin saw and caught without damage a large and beautiful Leucotheca. This was as big as the one that had exploded beneath me sixteen years earlier. All credit to their handling of this incredibly delicate creature, the men got it safely back to base and into our largest filming Kreisel tank. Once we had adjusted the flow, the big comb jelly began to expand its lobes and from within its folds it produced four truly science-fiction-inspired tentacles that swept the water on all sides. Being ciliated these tentacles flashed with refringent color, but paled into insignificance when the animal "switched-on" its main comb rows. "Switching-on" is not an exaggerated description. For all the world that is exactly what this Leucotheca seemed to do; it literally lit-up in an instant - flashed for thirty seconds or so, then switched off. We never could see how and why this took place - but it did.

This one animal gave all of us at the station many days and nights of unforgettable and spectacular display, feeding avidly on pteropods we supplied. To our huge satisfaction we managed successfully to keep this beautiful animal alive and well for the two weeks we wished to film it. We were keen to have it drift through frame while the camera was lined up on smaller members of the plankton community so that it would suddenly come surging up through frame, for all the world like some huge orbiting space station, flashing and pulsing as it passed. One curious feature of Leucotheca is that its main body is covered with transparent tubercles - as if it's been textured with rivets. One afternoon we decided it would a least be instructive and maybe dramatic to introduce one of our diminutive Beroe into the same tank. The Beroe was definitely hungry and prowled around the tank - eventually gliding up alongside the Leucotheca. Suddenly it turned and lunged with open lips at the main body of this forty-times-bigger monster. Its lips came into contact with the tubercles and immediately it "winced" and withdrew with its lips pursed like an old man without his dentures. We may never know, but it was our distinct impression that the tubercles produced something mildly poisonous or irritating to the Beroe.

During our second and third weeks, two other groups of intriguing animals drifted into our area of search and both gave us valuable material for the film. The first was two species of hydro-medusan, looking exactly like delicate jellyfish but characterized by spending part of their lives looking like plants attached to secluded overhangs of rock, often within caves. This is the vegetable or asexual part of their life. By a process of budding or release of discreet diminutive medusae these hydroid forms produce a very mobile and very predacious sexual phase. We collected large numbers of the two species, one of which seemed to attack and devour everything with which it came into contact including our precious comb jellies. The other species fed avidly upon the pteropods and salps that came in with every plankton haul. The other animal was for us a gift from heaven. We'd found them on previous trips and were well please to find them again. They were yet another species of comb jelly, but they were different. All full swimming species of comb jellies propel themselves by beating eight rows of fused cilia called combs, all, that is, but one. One has developed an extra trick - an escape routine unequalled by any other combjelly - it can flap and does so, so powerfully, that it can jet itself half a meter or so away and well out of danger. Since the main predator from which it attempts to escape is Beroe, this comb jelly, called Ocyropsis, was a natural to include in the sequence we were attempting to capture for "Island of Sharks". The added bonus with Ocyropsis is that if, as sometimes does occur, a Beroe succeeds in capturing one, then, as the predator engulfs its victim, the Ocyropsis goes on attempting to escape by furiously flapping. This produces action reminiscent of two small boys wrestling inside a pillowcase and that is exactly what we got, thirty foot across on the screen.

Mid expedition, one of our hauls brought in what at first we thought was a larval oar fish, the adult of which grows up to twenty two feet long and has only once been photographed in the open ocean. What we found we had actually caught was a no less attractive larval flounder, Bothus. Glassy transparent, an inch and half long, with a unicorn's "horn" on top of its head which it could raise or lower at will. In the Kreisel tank we were sure it would flee for the extremity and never be seen by the camera. Not a bit of it, it was a compulsive camera-hog! It didn't matter what we filmed, this little fellow kept wriggling into view, invariably backwards and always vertically with its head uppermost. We kept it going on a diet of fresh micro plankton for three full weeks before eventually liberating it back into the ocean.

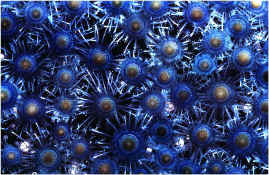

Finally, I was very much hoping that we would have a drift-by visit from some of the Neuston community - plankton that actually sit on, within or beneath the surface film of the sea. Heavy rain in our fourth week was punctuated by a flat calm and a leaden sky, but only the occasional light drizzle. Justin and I went out to the Deep Water channel and en route cut the engine to drift though a glassy slick off Palfrey island. Suddenly I spotted enormous specimens of Porpita amongst the Trichodesmium algal scum characteristic of warm calm tropical waters. In an hour we collected the biggest and best Porpita I'd ever seen in 30 years of study. They were so beautiful - hundreds of pale blue radiating tentacles and deep purple blue disc. Only days later we collected several smaller ones and filmed these as part of the microplankton predation sequence, as if in moonlight. Porpita is the exact opposite of benthic sea cucumbers in the ocean depths - awaiting for food to rain down from miles overhead. Porpita, at the surface, waits for food to upwell or migrate vertically from miles underneath. Usually considered to be a simple, highly-developed polyp Porpita, is a Chondrophoran and vaguely related to the Portuguese-Man-O-War.

The final couple of weeks of our trip, we were joined by Dr. Peter Herring - a senior Deep Sea Biologist based at the Southampton Oceanographic Centre in the UK. Peter is an old friend and the Marine Biologist I most respect for his breadth of knowledge. We'd invited him to join us - his first visit to the Australian Great Barrier Reef. He earned his keep by naming all sorts of odd things in the plankton and gave lots of help with collecting and feeding our precious charges. At the same time my old mate Roger Steene of "Coral Seas" fame came up from Cairns and joined us. Roger is a laugh a minute and over the years we've had some great times on Lizard Island together. He and Peter hit it off from the start and the humor ran high - not least when we ventured forth with cameras and dive gear to film a very large Cyanea Lion's Mane jellyfish that the maintenance engineer at the Research Station had caught early one morning in a "nally bin". Cyanea is a jellyfish-eating jellyfish, invariably accompanied by juvenile carangid fish. This one had more than three hundred fish which ducked and dived beneath its skirts.

It was very low tide as we left our mooring and we had to walk the Zodiac to deeper water. As we did so, I suddenly became aware that there were wind rows coming through the lagoon - one every twenty or thirty feet. Amongst the flotsam and jetsum were lots of dots - like dark colored seeds. I peered closer and only then recognized what it was. There were thousands upon thousands of dime-sized Porpita. The dark disk only the size of a pinhead. Roger went ballistic. He had always longed to find enough Porpita for him to get a wall-to-wall end paper for one of his books of solid blue Porpita. We collected and he photographed and his most recent book includes the shot. A humble postscript to this little finale. Because we were processing on site, we saw ours and Roger's results quickly. Chris Parks had decided to take a few shots of Roger's densely aggregated swarm of Porpita after they were free from Roger's attentions. Chris lit the shot differently. Roger's shots all came out with a vicious flare to one side where the light had caught the convex meniscus of the water - a touch more than brimful in the dish. Chris had lowered the level and backlit. His shots were superb. Roger, who spent most of one previous expedition slapping "made in Australia" stickers all over my optical bench, deserves the "Mick taking" I now inflict on him whenever we see a Porpita!

Thanks Howard and Michelle for the privilege of contributing to "Island of Sharks"

California Premier, June 1999, Imax Theatre, California Science Centre, Los Angeles |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||